#GipsotecaSMArt

Because of Covid-19 emergency, the Collection of Plaster Casts and Antiquities, together with the other museums of Sistema Museale di Ateneo, joins to the Ministry’s appeal and the campaign #iorestoacasa and #museichiusimuseiaperti, opening a virtual window to the collections and activities.

In this section you can find videos, images and downloading contents connected to the project GipsotecaSMArt, that will keep you company during the coming weeks. Follow our project on our site and Facebook with the official hashtag #GipsotecaSMArt.

The project is designed and supervised by Chiara Tarantino (Department of Civilisations and Forms of Knowledge) e Francesca Lemmi, jointly with di Stefano Landucci (Sistema Museale di Ateneo).

Our section

Starting from 4th April 2020, the Plaster Cast Collection of Antiquity s keeps its followers company with four new sections:

1. In a few words: it provides videos dedicated to sculptures, inspired by quotes from classical authors.

2. Originals and copies: it includes short articles and posts on the relationship between the plaster casts and the statues from which they have inspired.

3. What the statues don’t say: it shows posts for the youngest with memes and comics.

4. Find the statue: a social family game that encourage to observe, create and informally learn.

Originals and copies

The Laocoön’s arm (by Chiara Tarantino)

When the statue of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, constricted by the hug of two sea serpents together with his sons, was unearthed in Rome in 1506 it was not intact: Laocoön’s right arm, along with the children arms, and various sections of snake were missing.

Pope Julius II acquired the statue and the most famous artists of the time suggested his realist reconstruction.

Over the centuries, the original statue was reconstrued in various ways with different formal solutions, in particular Laocoön’s right arm and the serpents.

In 1906 Ludwig Pollak, academic and merchant, discovered the arm compatible with the arm of the group in the shop of a Roman stonemason; it took decades of studies and evaluations to guarantee that the fragment was original.

At the end of 1950s the “Pollak” arm was replaced to the reconstructed arm and the other addictions were dismantled: so, today the statue appears in the Vatican Museums as it is.

The Collection’s cast comes from the Vatican’s group before the addictions were dismantled, but in the following phase the copy of the right arm is inserted.

For more information:

- B. Andreae, Laocoonte e la fondazione di Roma, Milano 1989

- G. Bejor (a cura di), Il Laocoonte dei Musei vaticani: 500 anni dalla scoperta, Milano 2007

- F. Buranelli, P. Liverani, A. Nesselrath (a cura di), Laocoonte: alle origini dei Musei Vaticani, Roma 2006

- F. Donati, La Gipsoteca di arte antica, Pisa 1999, pagg. 202-211 S. Settis, Laocoonte. Fama e stile, Roma 1999

Marsyas, a surprised satyr (by Chiara Tarantino)

During 5th century B.C., the famous sculptor Myron mould the bronze into the statue of the satyr Marsyas, depicted while he was admiring the instrument that Athena firstly had been dreamt up and then threw it away, in the grip of rage. The instrument was a double flute similar to the recorder (aulos), due to which the goddess was mocked widely. While she was playing it, her cheeks bulged due to the effort and, on her first exhibition, the gods could not hold back the laughter.

During 5th century B.C., the famous sculptor Myron mould the bronze into the statue of the satyr Marsyas, depicted while he was admiring the instrument that Athena firstly had been dreamt up and then threw it away, in the grip of rage. The instrument was a double flute similar to the recorder (aulos), due to which the goddess was mocked widely. While she was playing it, her cheeks bulged due to the effort and, on her first exhibition, the gods could not hold back the laughter.

The original sculpture did not pass down to us, but we can have an idea of it thanks to the several marble copies that dates back to the 1st century B.C.

The best copy of these was found on the Esquiline Hill in 19th century, but it wasn’t linked immediately to the work of Myron, that at the time he was famous only for a notice of the Roman author Pliny the Elder. In the beginning, the pose of satyr, whose upper limbs were not preserved, was interpreted as a dancer and the statue was completed with arms and hands, playing castanets.

This version of the statue from Esquiline Hill is still admirable on the cast of the Collection of Plaster Casts, while the addictions were removed by the original, exhibited in the Vatican Museums.

For more information:

G. Daltrop, Il gruppo mironiano di Atena e Marsia nei Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano 1980

F. Donati, La Gipsoteca di arte antica, Pisa 1999, pagg. 161-163

C. Tarantino, Sacred. Ripensare l’arte antica, Pisa 2019, pagg. 14-17

C. Tarantino, Plinio, Pausania e un modello di Marsia. Riflessioni da una kylix del Museo Archeologico NazionaleTarquiniese in Agoge. Atti della Scuola di specializzazione in Beni archeologici dell’Università di Pisa, XIV-XV (2017-2018), Pisa 2020, in fase di stampa

A. Weis, Marsyas I in LIMC – LexiconIconographicumMythologiaeClassicae, Verlag, Zurigo-Monaco 1992, pagg. 366-378

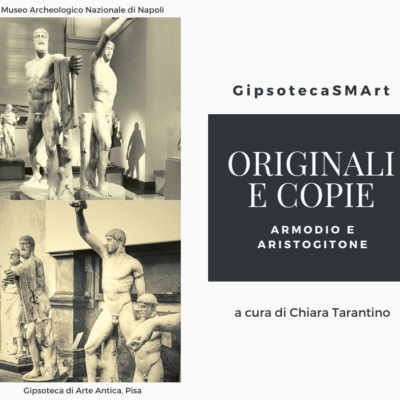

Harmodius and Aristogeiton killed the tyrant (by Chiara Tarantino)

The statues of the Athenians Harmodius and Aristogeiton exhibit in the Collection of Plaster Casts, are plaster casts of a sculptural group of the so-called Tyrannicides, coming from The National Archeological Museum of Naples.

These statues of Naples derive from a bronze sculpture made by Kritios and Nesiotes and dedicate in 477 B. C. from the Athenians to the heroes that some years before (in 514 B. C.) have killed Hipparchus.

We can only imagine the original sculptural group, lost today, thanks to the pictorial representations on the pottery or to the Roman copies.

We can only imagine the original sculptural group, lost today, thanks to the pictorial representations on the pottery or to the Roman copies.

Unfortunately, no copies are completed and the copy from Naples is the best and widely integrated with the reconstruction of the arms and part of the legs.

Fortunately, a part of the inscription, that was engraved into the base of the monument erected in the Agora, have been founded. The inscription said: “a big light rose up for the Athenians when Harmodius and Aristogeiton killed Hipparchus, freeing the homeland from tyranny”. The inscription is conserved in Athens in the Museum of the Ancient Agora.

For more information:

V. Azoulay, The tyrant-slayers of ancientAthens: a tale of twostatues, New York 2017

S. Brunnsäker, The Tyrant-Slayers of Krition and Nesiotes, s.l.s.ed. 1955

F. Donati, La Gipsoteca di arte antica, Pisa 1999, pagg. 153-156

M. W. Taylor, The TyrantSlayers: the heroic image in fifthcentury B.C. Athenian art and politics, Salem 1991

C. Tarantino, Sacred. Ripensare l’arte antica, Pisa 2019, pagg. 24-27

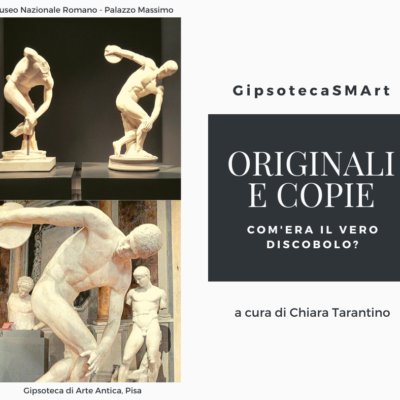

How was the real Discobolus? (by Chiara Tarantino)

The Discobolus is one of the most famous ancient sculpture, do we really know it?

We have in mind the sculpture’s pose, but we don’t know more about the statue chiselled by Myron of Eleutherae during the 5th century B.C. The original was in fact lost.

The Roman copies were identified thanks to description made by the Roman Autor Lucian (2th century A.D.): “the Discobolus is represented while he is about to throw the discus; his head is turned back to the hand that holds the discus, and tilted so as to snap back up”.

There are numerous and well-preserved copies, but they all are different: the body’s pose is similar but the position of the head, the face, the hairstyle and the muscles change.

The differences are accentuated if you observe them close up and one next to the other, such us in the National Roman Museum in Palazzo Massimo, where two of the best copies are conserved side by side.

The Collection of Plaster Casts’ version is an experiment, made up of parts of plaster casts coming from different copies.

For more information:

A. Anguissola, Fama, tema, forma: momenti della fortuna antica e moderna del “Discobolo” di Mirone in Prospettiva, 128 (2007), pagg. 26-42

A. Anguissola –S. Settis (a cura di), Serial/Portable Classic, Milano 2015

J. Boardman, GreekSculptures. The ClassicalPeriod, London 1991, pag. 80

F. Donati, La Gipsoteca di arte antica, Pisa 1999, pagg. 333-335

What the statues don’t say

Find the statue